February 16 / 17, 2022

By JoAnne Wadsworth, Communications Consultant, G20 Interfaith Forum

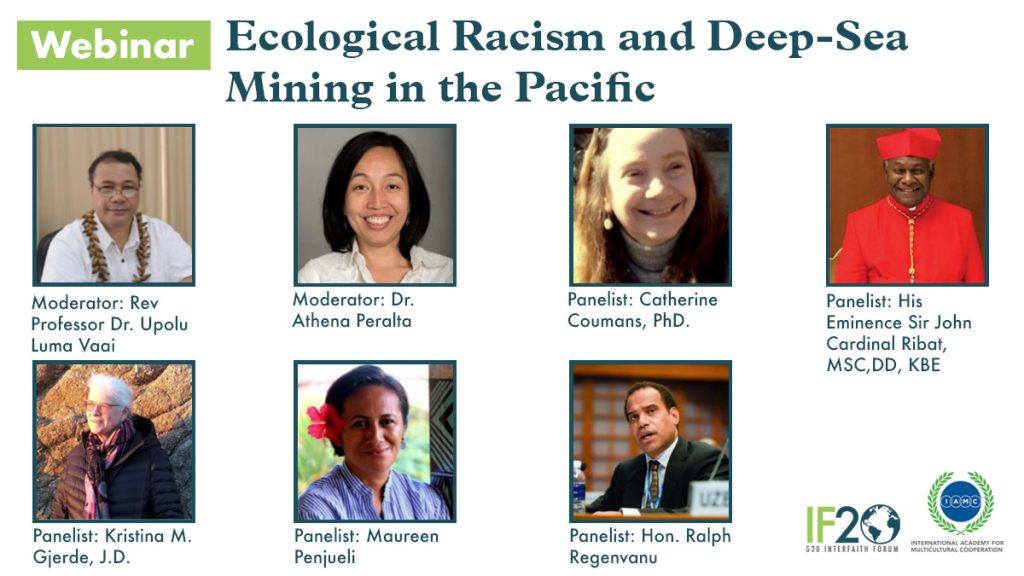

On Wednesday, February 16th, the G20 Interfaith Forum held its second webinar of 2022, organized by its Anti-Racism Initiative (in cooperation with several members of the IF20 Working Group on Environment) and co-sponsored by the International Academy for Multicultural Cooperation. Panelists included His Eminence Sir John Cardinal Ribat, MSC, DD, KBE, Metropolitan Archbishop of Port Moresby; Hon. Ralph Regenvanu, Member of Parliament and Leader of the Opposition Party for Vanuatu; Maureen Penjueli, Coordinator for the Pacific Network on Globalization (PANG); Dr. Catherine Coumans, PhD, Research Coordinator and Pacific Program Coordinator (Asia) at Mining Watch Canada; and Dr. Kristina M. Gjerde, Senior High Seas Advisor to IUCN’s Global Marine and Polar Programme. Rev. Dr. Upolu Luma Vaai, Principal of the Pacific Theological College and Professor of Theology and Ethics; and Athena Peralta, Programme Executive at the World Council of Churches, moderated the discussion. View the video recording of the webinar here.

Vaai began the discussion by welcoming all the panelists and audience members and outlining three objectives for the webinar’s discussions: To establish a link between Deep-Sea Mining (DSM) and Racism, to open critical conversations that honestly and courageously face the challenges of DSM, and to raise awareness as much as possible around the issue. Peralta added that the discussion would be formatted in the storyteller style of a Pacific “talanoa,” where speakers share both experiences and concerns in response to questions.

Catherine Coumans: What is Deep-Sea Mining?

“The reality that our deep ocean floor may actually be mined in the future is a shocking one. The deep seabed areas being targeted for mining are between 600M and 8KM in depth, and are the least-explored areas on Earth. More people have been to the moon than have been to these areas. These ecosystems are critical habitats for deep marine life that we know little about. They take millions of years to form, and once they’re gone, they’re gone.”

Coumans added that Pacific Nations can authorize DSM in their territorial waters, but for mining to happen in international waters, permits must be granted by the International Seabed Authority. 31 exploration permits have currently been issued to wealthy countries, who are behind the push for DSM—justifying it as a huge step forward for greener economies because many of the rare minerals used in technology manufacturing can be found on the ocean floor.

Maureen Penjueli: As a Pacific Islander and ocean activist, can you explain what you see as the impacts of DSM?

Penjueli said that the Pacific is often described as an underexplored, underexploited region of the world—and key to kickstarting the “blue economy.” She added that DSM is framed as having little to no impact and staggering benefits, but that people are not calculating the real costs of the practice.

“We live in an age where we know the cost of everything but the true value of absolutely nothing. We see things in terms of dollar signs. But it’s worth us thinking about cost in terms of what we will destroy: Unique deep-sea ecosystems that we don’t fully understand and which have taken millions of years to form. We’ll cause the mass extinction of deep-sea species which have survived for millennia. We need to calculate the real costs to ecology and biodiversity.”

Cardinal John Ribat: Why did the Papua New Guinea government opt for DSM, and how did the people, church, and indigenous communities respond?

Ribat said that the PNG government saw DSM as a “golden opportunity for revenue,” granting Mining Licensee 154 to a Canadian company in 2009 and buying 15% equity in the project. As PNG is already seen as a mining state, relying heavily on its natural resources as a source of GDP, it was more than willing to explore another form of mining. Since 2011, opposition to DSM has grown on grassroots levels, with coastal communities even launching legal proceedings against the PNG government in 2017 for access to the project documents.

“The environmental effects of mining are felt at local, regional, and even global scales. DSM will aggravate the present environmental crisis, not solve it. The destruction caused by DSM leads not only to the destruction of the ocean floor, but also to that of the entire ecosystem, including us as human beings.”

Kristina Gjerde: Can you explain some of the international laws and policies of the sea, and how they’re connected to DSM?

Gjerde said all laws and regulations surrounding the need to protect marine environments have happened in wake of The Law of the Sea Convention in the 1980s. At that convention, the seabed area was recognized as “the common heritage of humankind,” and the International Seabed Authority (ISA) was established with the charge to ensure an effective knowledge base so that future activities with DSM could be done in the right way.

Gjerde added that she’d been filled with excitement at the time, but she has since become entirely disillusioned about how the ISA has operated, as it is controlled by private interests and we continue to assault the ocean.

Catherine Coumans: In the case of policies like this, who should give consent? Should the actual grassroots communities who are stewarding these ocean areas have a say?

Coumans said that decisions were made to permit DSM in the 1980s and 90s—before many of the people who will be directly impacted by the practice were even born. In addition, the ISA is practically unknown and inaccessible, tucked away in Jamaica, and has complete autonomy in its right to carve up the seafloor and give it away to profit-seeking countries.

“These people are not seeking anyone’s consent, though they’re engaging in limited public ‘consultation.’ People can’t consider whether to give consent or not if they aren’t fully informed, but all communications surrounding DSM are trying to sell it. So who can we turn to in order to become better informed about the truth? Over 622 marine scientists and experts have signed a statement calling for a moratorium on DSM based on their in-depth knowledge of the costs and risks.”

Ralph Regenvanu: Racism can take many forms, including flowing through unfair economic systems. What are the potential risks of and links between DSM and racism?

Regenvanu asked participants to recognize that the Pacific is still the most colonized region of the Earth, and that islands were straitjacketed into the Western model of democratic nation-states in order to survive. As states are parasitic in nature, and can’t survive without taxation or resource extraction, Regenvanu said it is now the Pacific’s own indigenous leaders who are making the decision to go down the path of DSM due to the structure they exist in.

“I made a decision to go out and ask the people and make sure they knew what we were talking about when we referenced DSM. What we found at the end of talking to an informed public was that people were totally opposed to DSM now and forever.”

Maureen Penjueli: The Pacific is at the front line of impacts connected to the current climate emergency—but they could be hit by another crisis as the minerals needed to achieve the “green economy” the world is seeking can be found at the bottom of the ocean. Thoughts?

“On one hand, we’re considered the moral authority on the climate crisis, but we’re also going to be on the forefront of a race that nobody yet understands. We can’t be on the global scene arguing that we’re facing an existential crisis in the climate emergency while also being complicit about DSM.”

Penjueli added that the argument that DSM is “green” is a false one, since the consequences of harming the ocean could be disastrous: 83% of global carbon is circulated through the oceans, oceans absorb heat, and every second breath that we take is thanks to the functions of the ocean.

Kristina Gjerde: People are calling for a moratorium on DSM. What does that look like?

Gjerde said the IUCN adopted a resolution calling for a moratorium on DSM in September of 2021—calling for a stop to the practice “unless and until” the risks are fully understood and can be prevented, alternatives to deep-sea minerals in battery production have been found, the ISA structure is reformed to be open and transparent, etc.

“Scientists say we simply need many years of research in order to understand what we’ll lose if we open up DSM. A moratorium would help us buy ourselves time to contemplate, seek alternatives, and develop the scientific basis we need in order to actually have informed consent.”

Ralph Regenvanu: Should a moratorium be created to stop the mining “unless and until,” or should the Pacific simply say that mining has to stop?

“I personally think we need to take DSM off the menu completely so that Pacific Island countries can plan their futures without this as an option. But the people of the Pacific need to make this decision—with real, informed consent. To enable that, we need to utilize every measure we can to buy time, increase information, and get talking about this issue.”

Maureen Penjueli: Is it worth it to meet the needs of our present generation at the potential expense of future generations?

Penjueli said that one of the biggest challenges the Pacific has faced since DSM became part of the menu is that it’s been framed as the only option for GDP and there’s been a lack of other ideas. It’s been framed as “little to no impact and significant benefits,” and Pacific governments have seen these areas as belonging to the state and being unrelated to indigenous peoples.

“People simply make these assertions that DSM will improve GDP and we’ll benefit—but they haven’t proved that. And our communities have been expected to prove why it’s a problem. The burden of proof is in the wrong place. If our governments want to talk about development, then let’s talk about it. But if we’re only presented with one option, then that’s a problem.”

Cardinal John Ribat: As a leader of the Catholic Church in the Pacific, what key areas do you think we should improve to strengthen our collective ecological stewardship?

Ribat said that the people of the Pacific and the world need to unify, coming together to address an issue that affects all of us. He said this movement has begun on a Pacific level with churches coming together on common issues that affect them all, and that it needs to continue through educating individuals and communities on ecological stewardship.

“It’s in Laudato Si that we truly understand that churches have a responsibility to educate the people and be the voice of the unheard, ensuring that our environment is respected. There’s no insurance for our islanders when it comes to DSM. The only insurance is what we currently have: our life, and its connection to the sea. If we destroy that, we destroy ourselves.”

Conclusion

The webinar concluded with a very short Q&A session, then speakers offered brief concluding remarks after Arnie Saiki, a member of the IF20 Environment Working Group, summarized the discussion’s key points.

Vaai thanked all attendees and participants, then dedicated the webinar so that people might “see the world not in the light of money, but of life-giving interconnected relationships that foster justice.”

– – –

JoAnne Wadsworth is a Communications Consultant for the G20 Interfaith Association and acting editor of the “Viewpoints” blog.